| International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, ISSN 1927-1255 print, 1927-1263 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Int J Clin Pediatr and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://ijcp.elmerpub.com |

Original Article

Volume 14, Number 2, October 2025, pages 28-36

Determinants of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Children With Neurological Disorders: An Interdisciplinary Study

Giovani Ceron Hartmanna, Claudia Santos Oliveira Hartmannb, Gil Guilherme Gasparelloa, Mohamad Jamal Barka, Sergio Aparecido Ignacioa, Jacqueline de Almeida Antunes Rozysckia, Matheus Melo Pithonc, Robert Willer Farinazzo Vitrald, Orlando Motohiro Tanakaa, e

aMedicine and Life Science School, Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Parana, Curitiba, Brazil

bChild Neurology Department, Federal University of Parana, Curitiba, Brazil

cSouthwest Bahia State University - UESB, Vitoria da Conquista, Bahia, Brazil

dDepartment of Orthodontics, Juiz de Fora Federal University, Juiz de Fora - MG, Brazil

eCorresponding Author: Orlando Motohiro Tanaka, Medicine and Life Science School, Pontificia Universidade Catolica do Parana, Curitiba, Brazil

Manuscript submitted July 22, 2025, accepted October 4, 2025, published online October 22, 2025

Short title: OHRQoL in Children With Neurological Disorders

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/ijcp1017

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) is often compromised in children with neurological disorders, yet limited evidence exists on the contributing clinical and socioeconomic factors.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 132 children aged 6 - 14 years attending public neurology clinics. Parents or caregivers completed the validated Parental-Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ) and provided sociodemographic and health-related data.

Results: Most respondents were mothers (76.5%). High rates of bullying (78.6%) and dental caries (71%) were reported. Common diagnoses included epilepsy (49.2%), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (30.3%), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (26.5%). Poor OHRQoL was significantly associated with caregiver type (P = 0.046), low family income (P = 0.014), and living with relatives (P = 0.008). Functional limitations were the strongest OHRQoL domain (r = 0.780; P < 0.001). Children with cerebral palsy and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) exhibited the worst OHRQoL (P = 0.008). Although only 6.8% used orthodontic appliances, their presence negatively impacted OHRQoL.

Conclusions: Pediatric patients from lower-income families or non-parental households are at increased risk for impaired OHRQoL, especially those with cerebral palsy or ODD. Functional limitations, bullying, and untreated dental caries are key targets for clinical intervention in this vulnerable population.

Keywords: Oral health; Neurological disorders; Pediatrics; OHRQoL; Dental caries; Bullying; Developmental disorders

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The World Health Organization defines quality of life as an individual’s perception of their position in life in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns within the context of their culture and value systems [1]. As a multidimensional construct, it encompasses physical, psychological, and social dimensions of well-being.

Oral conditions such as malocclusion, dental caries, and periodontal disease are known to have profound clinical and psychosocial impacts, affecting essential functions like mastication, esthetics, and interpersonal interactions [2, 3]. The concept of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) reflects the individual’s perception of how oral health influences their daily functioning, emotional status, and social relationships [4].

In children with neurological or developmental disorders, self-reports are often not feasible, and OHRQoL is typically assessed through caregiver input. Tools like the Parental-Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire (P-CPQ) are validated for evaluating OHRQoL in children over 6 years old with psychomotor impairments [5, 6].

Understanding OHRQoL in this population is critical for guiding preventive and therapeutic oral health strategies, ensuring that care plans are responsive to the child’s broader psychosocial needs [7]. Research indicates that children with neurological disorders experience higher rates of dental caries, poorer oral hygiene, and limited access to preventive dental services compared to their typically developing peers [8, 9]. In particular, children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or intellectual disability (ID) often lack consistent fluoride applications, oral hygiene instruction, or dietary counseling [10].

Although pediatric research output is increasing, studies focusing on quality-of-life outcomes, particularly in children with neurological disorders, remain limited and often suffer from methodological inconsistencies, as highlighted in recent pediatric trial reporting guidelines [11].

Nonetheless, the relationship between OHRQoL and factors such as sociodemographic status, bullying, and clinical oral health indicators remains underexplored. A comprehensive assessment of these factors is necessary to understand the extent to which they affect daily life and well-being in this vulnerable group.

This study aims to evaluate the OHRQoL of children with neurological disorders and to examine the associations between clinical factors (e.g., caries, orthodontic needs), social determinants (e.g., bullying, caregiver type, family income), and specific neurological diagnoses. The study is designed to identify patterns and correlations among these variables without direct intervention or experimental manipulation, providing insights into factors that may influence OHRQoL in this population.

The study hypothesizes that clinical factors, such as dental caries and orthodontic along with sociodemographic variables including caregiver type, family income, and specific neurological diagnoses, are significantly associated with variations in OHRQoL among children with neurological disorders.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana (PUCPR) under protocol number 5.784.175 and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible institutional committee on human experimentation and with the principles of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Study design

A cross-sectional, observational study with a quantitative approach was conducted to assess OHRQoL in children with neurological disorders. Data were collected via a caregiver-completed questionnaire.

Sample size

Sample size was estimated using proportion sampling with a 95% confidence interval and P = 0.5 for maximum variability, resulting in a required sample of 76. To increase statistical power and reliability, 132 participants were ultimately included.

Participants

Children aged 6 - 14 years with neurodevelopmental disorders were recruited from two public neurology outpatient clinics at the Waldemar Monastier Children’s Hospital located in Campo Largo, Parana, and at the Wallace Thadeu de Mello e Silva Regional University Hospital, located in Ponta Grossa, Parana. Both institutions are affiliated with the Unified Health System (SUS) and were selected for their status as regional reference centers.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. Caregivers received detailed information regarding the study’s objectives, procedures, and potential risks, and were given the opportunity to ask questions before providing consent.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were children with a confirmed diagnosis of at least one of the following: ASD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), epilepsy, cerebral palsy (CP), ID, or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD).

Exclusion criteria

Caregivers with cognitive impairments precluding questionnaire completion and children receiving enteral feeding were excluded.

Data collection

Data were gathered using a 31-item online questionnaire (Google Forms) completed by caregivers. The questionnaire included demographic information, caregiver perceptions of OHRQoL, and reports of dental caries, orthodontic needs, and bullying. Informed consent was obtained electronically.

OHRQoL

The dependent variable was OHRQoL, assessed using the validated Portuguese short-form of the P-CPQ [12]. The 13 items are grouped into four domains: oral symptoms, functional limitations, emotional well-being, and social well-being. Responses used a five-point Likert scale and were dichotomized into “no impact” (never, once or twice) and “negative impact” (sometimes or more often) [13].

Independent variables

Dental caries

Dental caries was assessed based on caregiver responses to two binary questions about past decay and treatment history.

Bullying

Bullying was evaluated through three Likert-scale items adapted from the KIDSCREEN-52 [14] and was recorded as present if any item received an affirmative response.

Orthodontic need

Orthodontic need was determined using three questions regarding orthodontic appliance use, caregiver perception of need, and chewing discomfort. Responses were dichotomized; one positive response indicated need.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for sample characterization. Associations between OHRQoL and independent variables were tested using Chi-square analysis. Bivariate Poisson regression with robust variance estimated prevalence ratios. Variables with P < 0.20 were included in a multivariate hierarchical model; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Spearman’s correlation was used to evaluate domain relationships. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

| Results | ▴Top |

Demographics

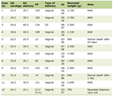

Caregivers of 132 children participated, with most respondents being mothers (76.5%), aged 18 - 44 years (69.7%), and reporting ≥ 18 h/day spent with the child (49.2%). Most families earned 1 - 3 minimum wages (59.8%), and 44.7% of caregivers had elementary education or less. Children were predominantly male (67.4%) and aged 6 - 10 years (58.3%), with 84.8% living with their parents (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Hierarchical Poisson Regression for Impact on P-CPQ of Children and Independent Variables |

Oral health and bullying

Dental caries were reported in 71% of children; 56.9% had never received dental treatment. Although 63.4% of caregivers perceived a need for orthodontic appliances, only 6.8% of children had received such treatment. Bullying was reported in 78.6% of cases, including teasing (70.1%), fear of peers (45.4%), and threats (40.3%).

Diagnoses

The most common diagnoses were epilepsy (49.2%), ASD (30.3%), ADHD (26.5%), ID (18.9%), CP (14.4%), and ODD (4.5%).

Statistical associations

Bivariate analysis showed significantly worse OHRQoL when responses came from relatives (P = 0.046), for children living with relatives (P = 0.008), and in families earning less than one minimum wage (P = 0.014). Poorer OHRQoL was also associated with CP, ODD (P = 0.008), and current orthodontic appliance use (P = 0.008).

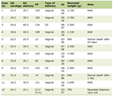

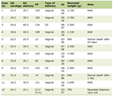

Multivariate analysis confirmed CP as a significant predictor of worse OHRQoL (P = 0.008). The average P-CPQ score was 12.48 ± 9.39 (range: 0 - 46) (Table 2). Spearman’s correlation showed that functional limitations had the strongest association with overall OHRQoL (r = 0.780, P < 0.001). All four domains were strongly intercorrelated (r = 0.60 - 0.90) (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 2. Prevalence of Negative Impacts on OHRQoL and Descriptive Statistics of P-CPQ Total and Domain Scores |

Click to view | Table 3. Spearman’s Correlation Coefficients Between P-CPQ Total Score and Its Domains (Oral Symptoms, Functional Limitations, Emotional Well-Being, and Social Well-Being) |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study assessed the impact of sociodemographic and oral health factors on OHRQoL in children aged 6 - 14 years with neurological disorders, using the validated short version of the P-CPQ questionnaire. To our knowledge, this is the first study to employ a hierarchical analytical approach linking OHRQoL to variables such as bullying, dental caries, and orthodontic treatment needs in this population.

Moreover, no eligible participants were lost or declined participation. All caregivers of children who met the inclusion criteria completed the questionnaires, ensuring full data coverage for the target population. This complete participation reduces concerns regarding potential bias related to caregiver engagement or willingness to participate.

Findings indicated that caregiver type significantly influenced OHRQoL, with non-parental caregivers (e.g., grandparents or aunts) reporting worse outcomes. Other predictors of poorer OHRQoL included low family income, non-parental living arrangements, and current orthodontic treatment.

Although dental caries and bullying were not statistically associated with lower OHRQoL scores, their prevalence exceeded 70%, considerably higher than in populations of typically developing children [15, 16]. This reinforces the disproportionate burden faced by children with neurological conditions.

The relationship between oral health and OHRQoL in children with neurodevelopmental disorders has been extensively explored over the last decade [2, 16-18]. For example, Abanto et al [19] demonstrated a significant negative impact of dental caries on OHRQoL among children with CP. In contrast, our findings did not show a statistically significant association between caries and OHRQoL, likely due to differences in measurement approaches, our study relied on caregiver-reported data rather than clinical assessments.

It is important to emphasize that using parents’ or caregivers’ perceptions to evaluate children’s health is valid, particularly in populations with neurological disorders where children may face communication barriers or lack a full understanding of their health status [20]. Given the outpatient neurology setting of this study, direct clinical examinations were not feasible, making caregiver-reported questionnaires the most practical and appropriate method for data collection. However, this study identified notable differences in reported OHRQoL when responses came from grandparents or aunts compared to parents, suggesting variation in caregiver perceptions.

Furthermore, family income and living arrangements were key determinants of OHRQoL. Children residing with extended family members (e.g., grandparents, siblings, uncles) experienced worse outcomes than those living with their parents. Similarly, families earning less than one minimum wage reported significantly lower OHRQoL than those earning between one and three minimum wages. These results are consistent with existing literature showing that family structure, economic stability, and social support systems are important contributors to children’s perceived well-being [21].

Socioeconomic status was a consistent determinant of OHRQoL. Children from low-income households and those living with extended family members had significantly worse quality of life, consistent with findings in previous studies [5, 19, 22]. Limited financial resources may restrict access to preventive dental care, oral health education, and follow-up treatment [5].

Although the sample was recruited from public health centers designated as regional reference clinics, the SUS is universally available to the entire population, regardless of socioeconomic status. In this study, the distribution of family income revealed comparable proportions of participants with higher income (above three minimum wages, 18.9%) and those with lower income (below one minimum wage, 21.2%).

Orthodontic treatment, typically associated with improved OHRQoL in healthy adolescents [23], was paradoxically linked to negative perceptions in this sample. This may reflect heightened pain sensitivity, behavioral barriers, or communication difficulties in children with neurological conditions [24].

Among diagnoses, children with CP and ODD exhibited the lowest OHRQoL. CP can cause spasticity and oral motor dysfunction, impairing eating and hygiene [6], while ODD is associated with behavioral resistance, potentially increasing the burden of dental care [25]. These effects may be amplified by environmental and socioeconomic inequities [26].

The average P-CPQ score (12.48 ± 9.39) was comparable to studies involving similar populations [27] but higher than in typically developing peers [6]. Common medications such as anticonvulsants may contribute to oral issues, including gingival hyperplasia [28], while logistical barriers - such as transportation and appointment delays, limit access to oral healthcare [29].

Consistent with the study hypothesis, the findings indicate that several clinical and sociodemographic factors are associated with variations in OHRQoL in children with neurological disorders. Specifically, non-parental caregiving, low household income, orthodontic treatment, and diagnoses such as CP and ODD were linked to poorer quality-of-life outcomes. In contrast, no statistical association was observed for dental caries and bullying, although their high prevalence underscores the need for targeted preventive strategies and psychosocial support.

This study should be interpreted in light of certain inherent limitations. It was carried out in a child neurology outpatient clinic, where several participants presented with multiple neurological diagnoses. Although this overlap is frequently observed in clinical practice, it complicates the identification of disorder-specific characteristics. Analyses involving children with neurological conditions should therefore take into account the possibility of co-occurring diagnoses. Furthermore, participants exhibited varying degrees of impairment, and all were analyzed collectively without stratification by specific symptoms or functional profiles, which may have influenced the interpretation of the findings.

In addition, this study relied solely on caregiver reports, without clinical validation of caries or orthodontic needs. Although this approach is suitable for outpatient settings with limited dental infrastructure, future research should incorporate clinical examinations to corroborate these findings and refine observed associations.

All information in the study was derived from the perceptions of parents and caregivers who completed the questionnaires, rather than from direct assessments or reports provided by the children themselves. Consequently, while the caregivers’ responses are expected to provide a reliable reflection of the children’s experiences and needs, they may not capture all aspects with complete precision. Subjective perceptions can be influenced by individual interpretation, recall bias, or limited observation of certain behaviors or symptoms, which means that the data should be considered as indicative rather than exact. Despite these limitations, caregiver reports remain a valuable source of information, particularly in outpatient settings where direct assessment may be constrained.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic status, caregiving structure, and specific neurological diagnoses are significant determinants of OHRQoL in children with neurological disorders. Children living with non-parental caregivers and those from low-income households experienced significantly worse OHRQoL. Orthodontic treatment was also associated with poorer outcomes, particularly among those diagnosed with CP and ODD. While dental caries and bullying did not show statistically significant associations, their high prevalence highlights the need for targeted oral health and psychosocial interventions in this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

GCH received a PhD scholarship from CAPES. OT holds a productivity grant from CNPq.

Financial Disclosure

This study received no financial support from any sponsor or funding agency.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Author Contributions

GCH, CSOH, SI, and OT conducted the literature review, constructed the questionnaire, collected data, and drafted the manuscript. GGG, MJB, and RWFV edited the manuscript. SI, MMP, JAAR and OT analyzed and interpreted the data and contributed to the discussion. GCH and OT conceived the study idea, provided guidance in the study design and coordination, and provided feedback on manuscript revisions. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- Prakash J, Das I, Bindal R, Shivu ME, Sidhu S, Kak V, Kumar A. Parental perception of oral health-related quality of life in children with autism. An observational study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021;10(10):3845-3850.

doi pubmed - Karimi P, Zojaji S, Fard AA, Nateghi MN, Mansouri Z, Zojaji R. The impact of oral health on depression: A systematic review. Spec Care Dentist. 2025;45(1):e13079.

doi pubmed - Goranson E, Sonesson M, Naimi-Akbar A, Dimberg L. Malocclusions and quality of life among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2023;45(3):295-307.

doi pubmed - Kragt L, van der Tas JT, Moll HA, Elfrink ME, Jaddoe VW, Wolvius EB, Ongkosuwito EM. Early caries predicts low oral health-related quality of life at a later age. Caries Res. 2016;50(5):471-479.

doi pubmed - da Silva ACF, Barbosa TS, Gaviao MBD. Parental perception of the oral health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2):1151.

doi pubmed - de Castelo Branco Araujo T, Nogueira BR, Mendes RF, Junior RRP. Oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: paired cross-sectional study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2022;23(3):391-398.

doi pubmed - Sruthi KS, Yashoda R, Puranik MP. Oral health status and parental perception of child oral health-related quality of life among children with cerebral palsy in Bangalore city: A cross-sectional study. Spec Care Dentist. 2021;41(3):340-348.

doi pubmed - Asiri FY, Tennant M, Kruger E. Oral health status of children with autism spectrum disorder in KSA: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2024;19(5):938-946.

doi pubmed - Konstantinova DA, Dimitorov LG, Angelova AN, Pancheva RZ. Components of oral health related to motor impairment in children with neuropsychiatric disorders. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e46093.

doi pubmed - Sherriff A, Stewart R, Macpherson LMD, Kidd JBR, Henderson A, Cairns D, Conway DI. Child oral health and preventive dental service access among children with intellectual disabilities, autism and other educational additional support needs: A population-based record linkage cohort study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2023;51(3):494-502.

doi pubmed - Baba A, Smith M, Potter BK, Chan AW, Moher D, Offringa M. Guidelines for reporting pediatric and child health clinical trial protocols and reports: study protocol for SPIRIT-Children and CONSORT-Children. Trials. 2024;25(1):96.

doi pubmed - Goursand D, Ferreira MC, Pordeus IA, Mingoti SA, Veiga RT, Paiva SM. Development of a short form of the Brazilian Parental-Caregiver Perceptions Questionnaire using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(2):393-402.

doi pubmed - Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Slade GD. Parental perceptions of children's oral health: the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:6.

doi pubmed - Guedes DP, Guedes JERP. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psycometric properties of the KIDSCREEN-52 for the Brazilian population. Rev Paulista de Pediatria, 2011;29:364-371.

- Iyanda AE. Bullying victimization of children with mental, emotional, and developmental or behavioral (MEDB) disorders in the United States. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2022;15(2):221-233.

doi pubmed - Qiao Y, Shi H, Wang H, Wang M, Chen F. Oral health status of Chinese children with autism spectrum disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:398.

doi pubmed - Salerno C, Campus G, Bonta G, Vilbi G, Conti G, Cagetti MG. Oral health-related quality of life in children and adolescent with autism spectrum disorders and neurotypical peers: a nested case-control questionnaire survey. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2025;26(2):299-310.

doi pubmed - Weckwerth SA, Weckwerth GM, Ferrairo BM, Chicrala GM, Ambrosio AM, Toyoshima GH, Bastos JR, et al. Parents' perception of dental caries in intellectually disabled children. Spec Care Dentist. 2016;36(6):300-306.

doi pubmed - Abanto J, Ortega AO, Raggio DP, Bonecker M, Mendes FM, Ciamponi AL. Impact of oral diseases and disorders on oral-health-related quality of life of children with cerebral palsy. Spec Care Dentist. 2014;34(2):56-63.

doi pubmed - Loytomaki J, Laakso ML, Huttunen K. Social-emotional and behavioural difficulties in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: emotion perception in daily life and in a formal assessment context. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023;53(12):4744-4758.

doi pubmed - Chan KL, Chen M, Chen Q, Ip P. Can family structure and social support reduce the impact of child victimization on health-related quality of life? Child Abuse Negl. 2017;72:66-74.

doi pubmed - Du RY, Yiu CKY, King NM. Health- and oral health-related quality of life among preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2020;21(3):363-371.

doi pubmed - Abreu LG, Melgaco CA, Lages EM, Abreu MH, Paiva SM. Parents' and caregivers' perceptions of the quality of life of adolescents in the first 4 months of orthodontic treatment with a fixed appliance. J Orthod. 2014;41(3):181-187.

doi pubmed - McKeown CA, Vollmer TR, Cameron MJ, Kinsella L, Shaibani S. Pediatric pain and neurodevelopmental disorders: implications for research and practice in behavior analysis. Perspect Behav Sci. 2022;45(3):597-617.

doi pubmed - Jamali Z, Ghaffari P, Aminabadi NA, Norouzi S, Shirazi S. Oral health status and oral health-related quality of life in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Spec Care Dentist. 2021;41(2):178-186.

doi pubmed - Zeidan J, Fombonne E, Scorah J, Ibrahim A, Durkin MS, Saxena S, Yusuf A, et al. Global prevalence of autism: a systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022;15(5):778-790.

doi pubmed - Nqcobo C, Ralephenya T, Kolisa YM, Esan T, Yengopal V. Caregivers' perceptions of the oral-health-related quality of life of children with special needs in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health SA. 2019;24:1056.

doi pubmed - Gallo C, Bonvento G, Zagotto G, Mucignat-Caretta C. Gingival overgrowth induced by anticonvulsant drugs: A cross-sectional study on epileptic patients. J Periodontal Res. 2021;56(2):363-369.

doi pubmed - Verma A, Priyank H, Viswanath B, Bhagat JK, Purbay S, V M, Shivakumar S. Assessment of parental perceptions of socio-psychological factors, unmet dental needs, and barriers to utilise oral health care in autistic children. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e27950.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.