| International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, ISSN 1927-1255 print, 1927-1263 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Int J Clin Pediatr and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://ijcp.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 2, October 2025, pages 55-59

Anomalous Right Coronary Artery in a Cyanotic Two-Month-Old Infant

Aya Majzouba, b, Yasser Elhashasha, b, Leif Loviga, b, Lily Q. Lewa, b, c

aDepartment of Pediatrics, Flushing Hospital Medical Center, Flushing, NY 11355, USA

bThese authors contributed equally to this article.

cCorresponding Author: Lily Q. Lew, Department of Pediatrics, Flushing Hospital Medical Center, Flushing, NY 11355, USA

Manuscript submitted July 9, 2025, accepted October 7, 2025, published online October 17, 2025

Short title: Anomalous Right Coronary Artery in an Infant

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/ijcp1013

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Cyanosis is relatively common in infants and may suggest a cardiovascular or respiratory cause. Of the cardiovascular causes, cyanosis is not typically associated with anomalous origin of a coronary artery. Congenital coronary artery anomalies are rare and often discovered incidentally on transthoracic echocardiography. We describe a cyanotic infant with anomalous origin of the right coronary artery that was identified on transthoracic echocardiography.

Keywords: Anomalous right coronary artery; Cyanosis; Infant

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cyanosis refers to a bluish discoloration of the skin due to the increase of deoxygenated hemoglobin. This clinical sign in infants suggests a cardiovascular or pulmonary cause. An infectious, neurologic, metabolic or hematologic cause is also possible [1]. Healthcare providers in the emergency department face the challenge of requesting appropriate laboratory and imaging tests, obtaining timely referrals, and achieving expeditious disposition. A rapid and accurate diagnosis and management will support an optimal outcome.

A thorough medical history and findings on physical examination help narrow the differential diagnoses. It is critical to diagnosis any potentially life-threatening condition early. Although a heart murmur may suggest a cardiovascular diagnosis, heart murmurs in children are common and generally benign [2]. However, in this case, the combination of cyanosis and a nonspecific heart murmur led to an echocardiogram, which proved to be diagnostic. An anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the opposite sinus classifies this finding as a congenital anomaly of the coronary artery [3]. The absence of symptoms often makes the diagnosis a challenge [4]. A transthoracic echocardiogram can be used to identify the origin of the coronary arteries regardless of symptoms, especially in the pediatric population. There exists a paucity of data on cyanosis associated with an anomalous origin of the coronary artery. This case report highlights the atypical presentation of cyanosis in the setting of an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 2-month-old Hispanic male infant presented to the emergency department with reported intermittent cyanotic choking episodes for 3 days. For 2 days, he had been experiencing rhinorrhea and nasal congestion that was not accompanied by fever. He had no household members with illness. He was offered and tolerated 120 to 180 mL of formula every 3 h. He had no history of vomiting, stiffening, or abnormal movements. The pregnancy had been complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus that did not require any treatment. A fetal echocardiogram performed at 22 weeks of gestation did not reveal any cardiac defect. He was born at 38 weeks of gestation via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery with Apgar scores of 9 at one and 5 min and birth weight of 3,820 g. He had an uneventful neonatal course. His family history was negative for a chronic cardiac or lung condition.

On physical examination, he was in no acute distress and was not cyanotic when crying. The facies was not dysmorphic. He had a weight of 6.30 kg (86th percentile), length of 62.0 cm (97th percentile), blood pressure of 81/43 mm Hg, pulse of 138 beats per minute (bpm), respiratory rate of 36 breaths per minute, temperature of 36.1 °C, peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 100% in room air and capillary filling less than 2 s. Cardiorespiratory examination demonstrated a grade II-III/VI non-radiating vibratory systolic murmur along the left sternal border and lungs clear on auscultation. Hepatosplenomegaly was not appreciated on palpation of the abdomen.

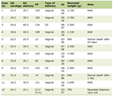

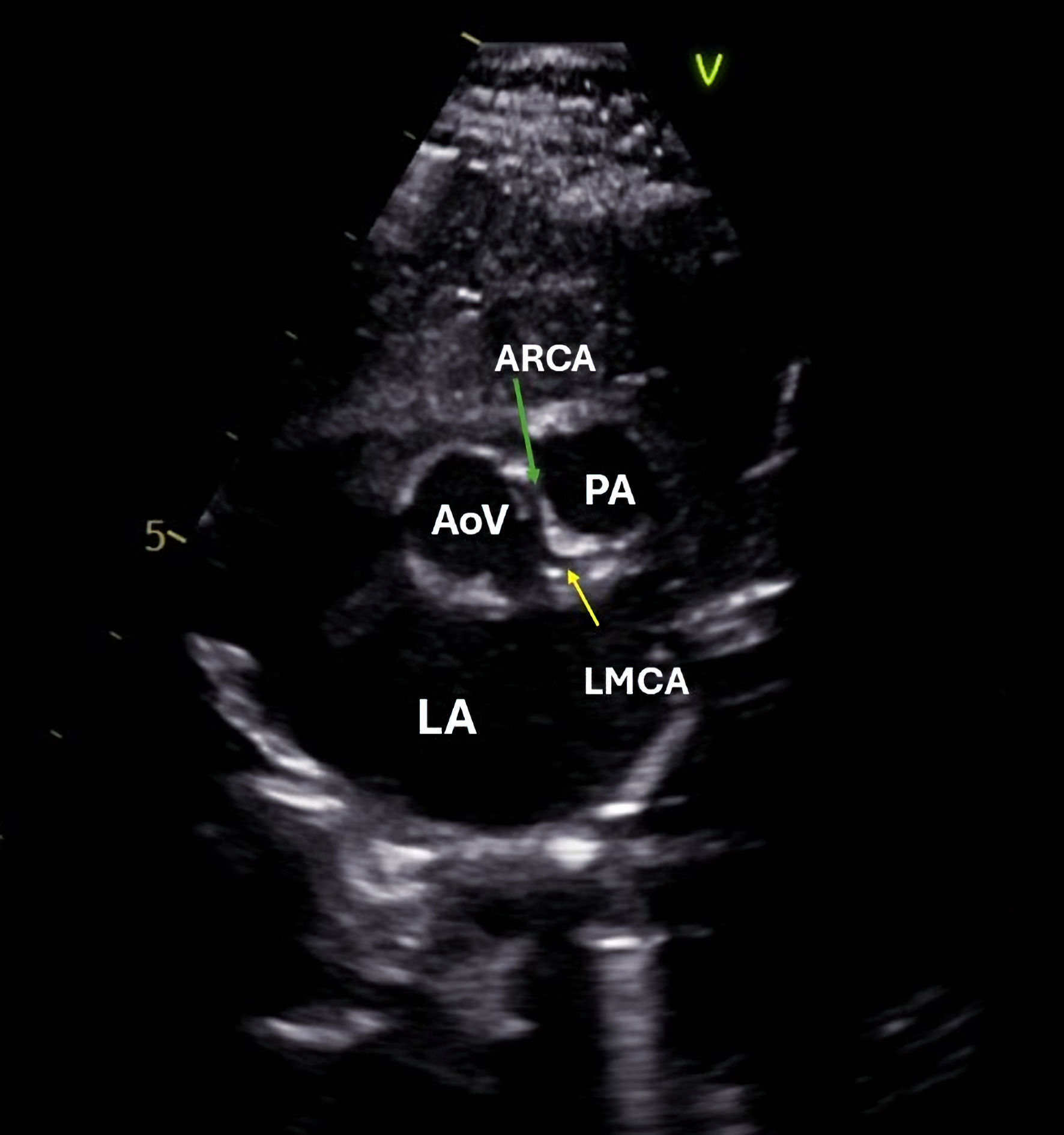

Laboratory investigations are shown in Table 1. Chest radiograph showed a normal cardiothymic silhouette and mild hyperinflated lung fields. Electrocardiogram traced normal sinus rhythm and rate, and without abnormalities in ST- and T-waves. The mean SpO2 (%) and standard deviation (SD) by continuous pulse oximetry on the foot was 98.7 (SD = 1.5). Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery with interarterial course and a small patent foramen ovale were identified on transthoracic echocardiogram (Fig. 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Investigations |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrated right coronary artery arising from the left coronary cusp on cross-sectional parasternal short axis view. The yellow and green arrows indicate the LMCA and ARCA, respectively. AoV: aortic valve; ARCA: anomalous right coronary artery; LMCA: left main coronary artery; PA: pulmonary artery; LA: left atrium. |

The patient had an unremarkable clinical course during the 3 days of in-patient observation. Instructions on infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation were given to the parents before hospital discharge. Advanced imaging studies including computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging were deferred. Conservative management with close clinical follow-up with the pediatric cardiologist was recommended pending risk stratification of the anomaly. On his 1-year follow-up, our patient demonstrated normal growth and development.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Cyanosis in young infants is relatively common and can be associated with a potentially life-threatening cardiovascular or pulmonary cause [1]. The family that encounters this unexpected blue skin discoloration on any part of the body usually seeks immediate medical evaluation. A thorough history and physical examination can identify risk factors and initiate appropriate tests for early diagnosis, and optimal management and outcomes. For example, a history of gestational diabetes mellitus increases risk for large for gestational age, polycythemia and congenital heart disease [1]. Our patient’s birth history and immediate neonatal history were uneventful. The infant was discharged from the newborn nursery excluding complications attributed to gestational diabetes mellitus. A basic evaluation in the emergency department including complete blood count, serum electrolytes, chest radiograph and electrocardiogram can eliminate several causes of intermittent cyanosis based on characteristic findings. For example, a boot shaped heart on chest radiograph is typical of tetralogy of Fallot, right axis deviation detected on electrocardiogram is predictive of pulmonary hypertension, or a misdiagnosis of pneumonia when arteriovenous malformations exist [1].

On hospital admission, the pediatric cardiologist was consulted to address the combination of cyanosis and a nonspecific heart murmur on auscultation. The fetal echocardiogram was negative for congenital heart defects. The chest radiograph and 12-lead electrocardiogram were not diagnostic. Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left coronary cusp with interarterial course was detected on two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiogram.

Anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left coronary cusp represents a rare congenital coronary artery anomaly with a prevalence of 0.1-1.0% [4]. The spectrum of clinical presentations of this cardiovascular anomaly spans from asymptomatic to sudden cardiac death. Cyanosis rarely occurs with anomalous origin of coronary arteries. Due to the heterogeneous clinical presentations of this cardiovascular disease, the reported prevalence may be underestimated, which contributes to the paucity of studies on the management and prognosis of this condition in young children [5]. Coronary artery anomalies consist of a group of anomalies classified and designated according to the origin, course, termination, and size of the epicardial coronary arteries [6]. Transthoracic echocardiogram provides a non-radiation and noninvasive initial imaging modality for the identification of coronary artery origin [7]. We identified the anomaly on cross-sectional parasternal short axis view by placing the ultrasound transducer on the anterior chest left of the mid-sternum. Advanced imaging modalities such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are used to define the anatomy and risk stratification of this anomaly [8]. Early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate risk stratification supply essential data for guiding management decisions and optimizing outcomes in those affected. The risk of sudden cardiac death remains unknown and has been often associated with exertion such as in sports or vigorous exercise as in a young athlete [8]. An anomalous right coronary artery originating from the opposite sinus presents several folds more commonly than left coronary artery originating from the opposite sinus and may be considered of lower risk of adverse clinical events. Whereas, having an interarterial course and long intramural component are associated with higher risk of sudden cardiac death [6, 9]. Our patient was not assigned a specific risk classification pending advanced imaging studies. We are mindful that identifying the risk for sudden cardiac death is crucial before participation in sports and vigorous exercise.

Although most patients with this condition have no symptoms, difficulty in feeding, poor weight gain, and heart failure have been reported in infants with coronary artery anomalies [10]. Our patient was thriving. Overfeeding, poor feeding technique, and gastroesophageal reflux disease were considered and excluded as a possible cause of choking. In a case series of nine patients with an anomalous right coronary artery ranging in age from 3 months to 12 years by Na et al, only the youngest patient presented with cyanosis, which is similar to our patient [11]. The small patent foramen ovale in our patient is unlikely to cause the observed cyanosis or heart murmur. Our patient did have rhinorrhea and nasal congestion typical of adenovirus infection, but cyanosis is atypical of adenovirus infection. Our patient also did not have hypoxia or myocardial ischemia. A viral illness may have allowed for the expression of a cardiac insufficiency-related symptom such as cyanosis [11]. A possible mechanism for the cyanosis in our young patient is a higher intermittent metabolic demand during a viral illness. Without a viral infection, our patient may have remained asymptomatic and undiagnosed until adolescence or adulthood. Thus, infants testing positive for a respiratory virus and having cyanosis should be thoroughly evaluated, including a complete transthoracic echocardiogram for coronary artery anomalies. A bacterial infection or inflammation is unlikely in the setting of a normal white blood cell count and differential, and C-reactive protein level, respectively, in our case.

We report a single case highlighting the atypical presentation of anomalous coronary artery and the relevance of transthoracic echocardiogram. Determining risk stratification of this anomaly following advanced imaging studies can facilitate definitive management decisions and impact both the patient’s and family’s quality of life. Establishing a multidisciplinary team remains critical in the care of this infant to ensure an optimal outcome.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Oliver Fultz for his editorial support.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the guardian (mother) has given her consent for her child’s images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal.

Author Contributions

AM cared for the patient and was responsible for conception/design, literature search, data interpretation, drafting and revision of the manuscript, and preparation of the figure. YE was responsible for conception/design, literature search, drafting and revision of the manuscript. LL cared for the patient, and was responsible for data interpretation, drafting and revision of the manuscript and preparation of the figure. LQL was responsible for conception/design, literature search, data interpretation, preparation of the figure, drafting, editing, revising and submitting the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Fayyaz M, Shahbaz S. A narrative review on management of cyanosis in neonates: management of cyanosis in neonates. Pakistan Journal of Health Sciences. 2023;4(11):14-19.

- Gonzalez VJ, Kyle WB, Allen HD. Cardiac examination and evaluation of murmurs. Pediatr Rev. 2021;42(7):375-382.

doi pubmed - Doan TT, Puelz C, Rusin C, Molossi S. Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery in pediatric patients. Curr Pediatr Rep. 2024;12(3):69-80.

doi pubmed - Brothers JA, Frommelt MA, Jaquiss RDB, Myerburg RJ, Fraser CD, Jr., Tweddell JS. Expert consensus guidelines: Anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(6):1440-1457.

doi pubmed - Gentile F, Castiglione V, De Caterina R. Coronary artery anomalies. Circulation. 2021;144(12):983-996.

doi pubmed - Adam EL, Generoso G, Bittencourt MS. Anomalous coronary arteries: when to follow-up, risk stratify, and plan intervention. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23(8):102.

doi pubmed - Davis JA, Cecchin F, Jones TK, Portman MA. Major coronary artery anomalies in a pediatric population: incidence and clinical importance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):593-597.

doi pubmed - Molossi S, Sachdeva S. Anomalous coronary arteries: what is known and what still remains to be learned? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2020;35(1):42-51.

doi pubmed - Okoli SE, Chiang M, Hattendorf B, Reddy SCB. Incidental diagnosis of anomalous origin of right coronary artery from the contralateral (left) sinus of valsalva in a child: sonographer and physician perspectives. CASE (Phila). 2022;6(7):321-323.

doi pubmed - Feng J, Zhao J, Li J, Sun Z, Li Q. Classification, diagnosis and clinical strategy of congenital coronary artery disease in children. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1132522.

doi pubmed - Na J, Chen X, Zhen Z, Gao L, Yuan Y. Anomalous right coronary artery originating from the aorta: a series of nine pediatric cases. BMC Pediatr. 2023;23(1):546.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.