| International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics, ISSN 1927-1255 print, 1927-1263 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Int J Clin Pediatr and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://ijcp.elmerpub.com |

Case Report

Volume 14, Number 1, June 2025, pages 7-12

Surgical Repair of an Idiopathic Pediatric Popliteal Artery Aneurysm

Ishtiaq Aziza, Tariq Alib, Philip C. Bennetta, c

aNorfolk and Norwich Vascular Unit, Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital, Norwich NR4 7UY, UK

bNorfolk Centre for Interventional Radiology, Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital, Norwich NR4 7UY, UK

cCorresponding Author: Philip C. Bennett, Norfolk and Norwich Vascular Unit, Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital, Norwich NR4 7UY, UK

Manuscript submitted March 11, 2025, accepted May 23, 2025, published online May 30, 2025

Short title: Pediatric Popliteal Pseudoaneurysm Repair

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/ijcp1006

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Popliteal artery pseudoaneurysms are uncommon in young individuals, especially without an underlying connective tissue disorder. We present a case of a 14-year-old female who presented with acute lower limb ischemia due to a popliteal artery pseudoaneurysm. The patient had no personal or family history of a connective tissue disorder. Following radiological confirmation of diagnosis and reviewing the available literature on the topic, the child underwent open surgical intervention with a great saphenous vein interposition graft resulting in limb salvage. Intraoperative specimens underwent histological and microbiological examination and no evidence of infection, connective tissue disorder, or vasculitis was identified. The patient subsequently underwent genomic sequencing which did not identify any potential causative factors. This case highlights the importance of considering rare vascular pathologies in young patients presenting with acute limb ischemia. While the evidence base is sparse, the most common management of symptomatic pediatric aneurysms/pseudoaneurysms is open surgical interposition graft repair using autologous great saphenous vein and therefore we recommend this modality for treating this unusual presentation.

Keywords: Pediatric; Popliteal artery; Aneurysm; Pseudoaneurysm; Interposition graft

| Introduction | ▴Top |

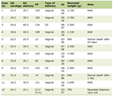

Idiopathic lower limb aneurysms are a rare entity in the pediatric population, with only a handful of reported cases in the literature, illustrated in Table 1 [1-13]. There have previously been cases reported to be secondary to blunt and penetrating trauma [4, 14], hereditary exostosis [15], infection [16], and osteochondroma [17]. In previous instances, idiopathic pediatric popliteal pseudoaneurysms (IPPPs) have also been reported [1-3]. The most common presentations were acute limb ischemia, leg pain, pulsatile swelling with or without foot drop. Previous cases were all managed with open surgical repair with excision of popliteal aneurysm and end to end anastomosis or bypass using vein or Dacron via either a medial or posterior approach. We report a further case of IPPP and its surgical management.

Click to view | Table 1. Review of the Literature of Cases of Pediatric Popliteal Artery Aneurysm/Pseudoaneurysm |

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 14-year-old girl was referred to the venous thromboembolism (VTE) clinic following general practitioner (GP) review, with a 4-day history of pain in her right calf and pain and paresthesia in her right foot. There was no documentation of peripheral pulse status in the patient clinical records from the GP, and the initial differential diagnosis was deep vein thrombosis (DVT), which prompted a referral to hospital for venous duplex scanning the same day. Initial imaging was negative for DVT but reported focal increased echogenicity in the gastrocnemius muscle at the point of maximum tenderness, which may represent a focal muscle sprain or tear. The report prompted a referral to the pediatric team the same day who did not document any assessment of peripheral pulses but made a further referral to the orthopedic team who reviewed the patient on the same evening. The documented orthopedic clinical assessment revealed an expansile and pulsatile swelling in the popliteal fossa and absent right-sided foot pulses and they subsequently made a referral to the vascular surgery team who reviewed the patient on the same evening. On reviewing the history, the patient had denied any recent or previous blunt trauma to her popliteal fossa and no recent history of infection. The patient had been asymptomatic up until date of index symptom, whereafter she had difficulty mobilizing due to pain. She had been systemically well, was apyrexial, and inflammatory markers were within normal range. There was no family history of connective tissue disorders, and the patient had no phenotypical features of these.

Given this unusual presentation in a pediatric patient, we wanted to confirm our working diagnosis of a popliteal aneurysm, assess for any other aneurysms, and need cross-sectional imaging to plan surgical intervention. Magnetic resonance imaging was not considered due to difficulties in obtaining this at our institution and the need for prompt intervention. Following consultation with the pediatric and radiology teams, a computed tomography (CT) scan of whole aorta and peripheral angiogram was performed, demonstrating a 3.7 cm wide-necked saccular aneurysm (Fig. 1) arising from the second segment of the popliteal artery. There was some focal calcification within the aneurysm wall, suggesting that it may not be entirely acute. There was also irregular thrombus within the aneurysm sac and downstream focal occlusion of the anterior tibial artery and the posterior tibial artery at the ankle with poor flow into the foot secondary to distal embolization. No evidence of visceral or large vessel aneurysm was identified.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Coronal multi-planar reconstruction of the lower limb vessels demonstrating the right popliteal pseudoaneurysm (arrow). |

In-depth discussions were made with the patient and her parents about the rare diagnosis and its etiology, the need to send specimens for histological and microbiological assessment, the risks of complications from surgery, likely post-operative stay, need for antiplatelet therapy, and post-discharge graft surveillance. The patient was at an age where she could understand what was going on and indeed co-signed the consent form once the decision to operate was made.

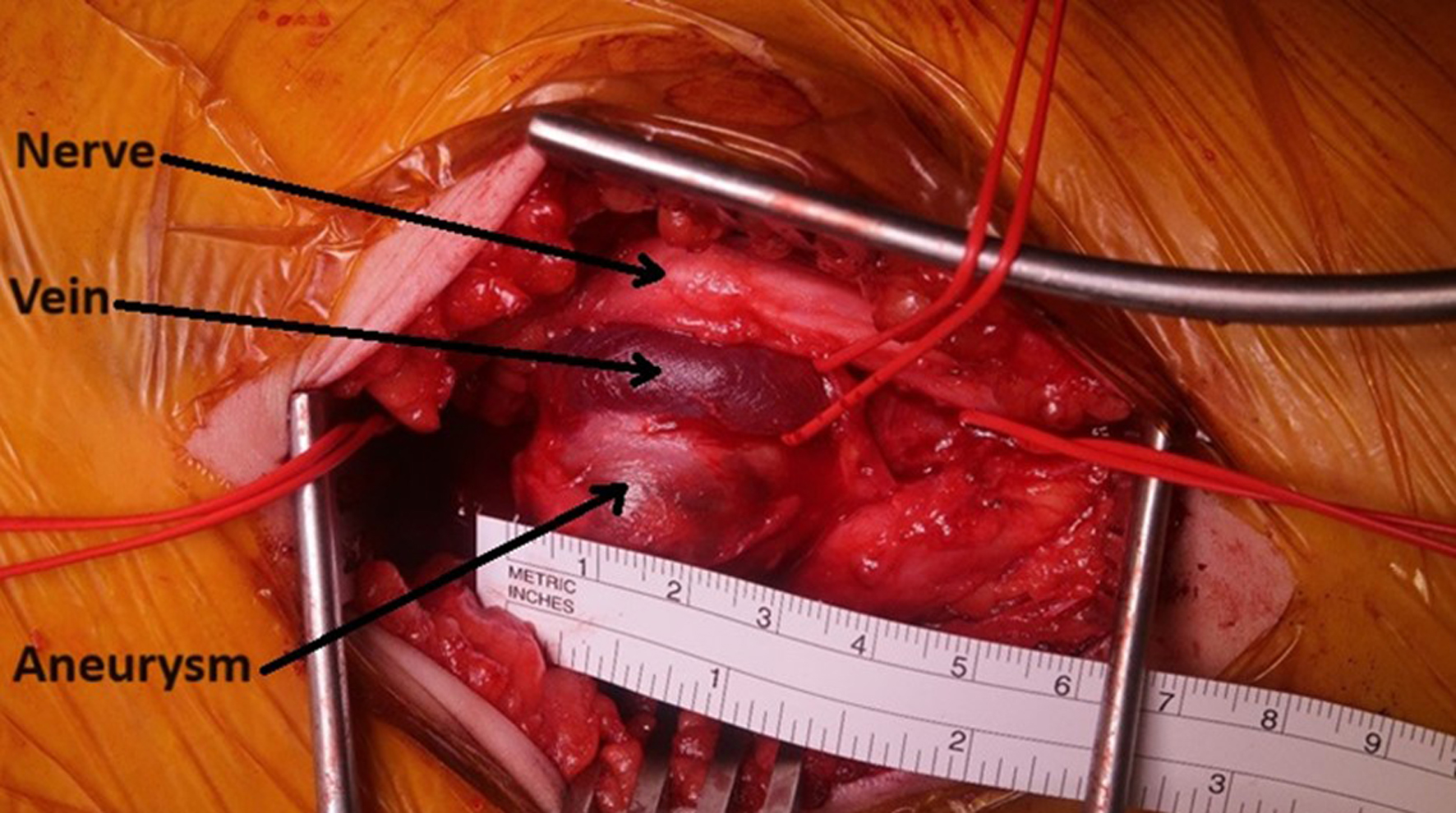

A decision was made to use a posterior approach to explore her popliteal artery, obtain specimens, washout the wound, and perform vascular reconstruction. Following induction of anesthesia, the patient was positioned prone with the knee slightly flexed. The great saphenous vein (GSV) was scanned on the operating table and marked, as was the position of the popliteal pseudoaneurysm and normal proximal and distal vessel. A vertical incision was made over the popliteal artery and proximal and distal vascular controls were obtained prior to exploration of the pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Popliteal pseudoaneurysm visible via posterior surgical approach. |

Following systemic heparinization, proximal and distal popliteal artery was clamped. The pseudoaneurysm was tethered to the popliteal vein which was mobilized where possible but where dissection of the sac would have increased the risks of venous injury this was left. While there were no features to suggest a mycotic pseudoaneurysm, sac and thrombus were sent for histological and microbiological assessment prior to irrigating the wound with saline.

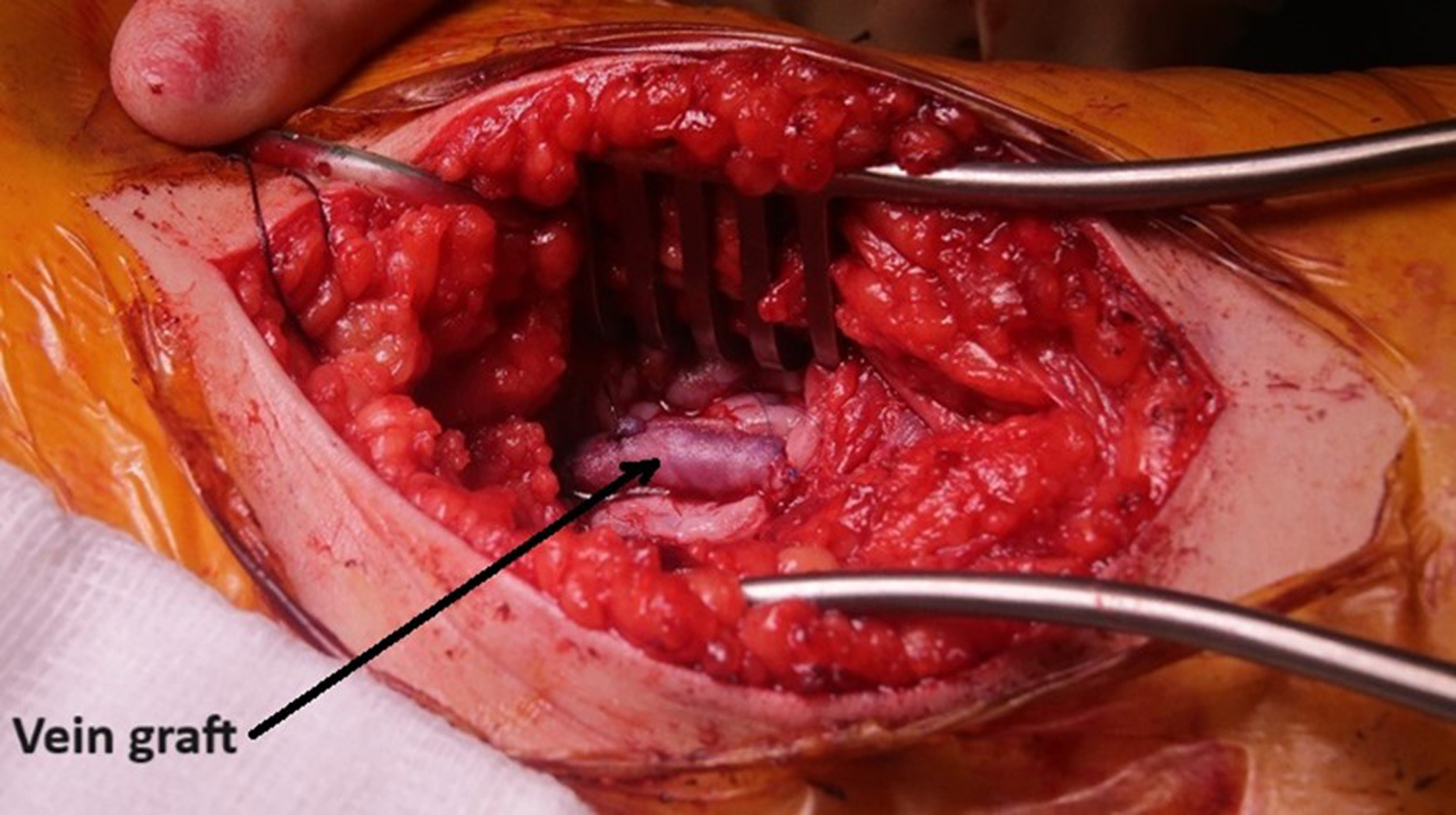

The wide neck was not suitable for primary closure and so a popliteal interposition graft using reversed GSV was performed using a continuous 7/0 Prolene suture (Fig. 3). Prior to performing the anastomoses, a Fogarty embolectomy catheter was passed distally in an attempt to improve the inflow into her foot. However, we were unable to pass the distally thrombosed vessel. Following the surgical repair and removal of drain, the patient’s foot pain and paresthesia resolved. She remained in hospital for 3 days post-operatively and was discharged home with a 3-month course of aspirin. Microbial culture was negative at 48 h and histological evaluation demonstrated no convincing medial myxoid degeneration of the wall, no granulomas, fungal elements or evidence of active vasculitis or malignancy. They concluded no specific features to indicate etiology.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Interposition graft repair using reversed great saphenous vein. |

At 6-week follow-up review, the wounds had completely healed, and the patient had resumed physical exercise classes at school. Duplex ultrasound on the day of this follow-up review (one stop surveillance scan) demonstrated the interposition graft and both anastomoses to be patent, with no stenoses with good volume triphasic flow seen in the distal below knee popliteal artery. The patient will continue with ultrasound surveillance for at least 12 months. The patient was subsequently reviewed in a regional clinical genetics clinic and no evidence of connective tissue abnormalities has been found.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

IPPP has only been previously reported in a handful of cases and reported to be secondary to blunt and penetrating trauma [4, 14], hereditary exostosis [15], infection [16], and osteochondroma. While we likely will never know why this patient developed this diagnosis, given the calcification within the aneurysm wall, our theory is that the patient may have sustained blunt trauma to her popliteal fossa in her distant past and could not remember this happening.

A meta-analysis including only one small randomized controlled trial comparing outcomes of endovascular versus open repair in the management of asymptomatic adult popliteal artery aneurysms found no difference in assisted or unassisted patency at 4 years follow-up [18]. No previous cases of IPPP management opted for an endovascular approach, and we do not think endovascular repair in a symptomatic or pediatric patient would be appropriate due to the discrepancy in size of stent and artery as the child grows and the need for long-term antiplatelet therapy. In our case, we were also unsure of any infective etiology and so did not want to insert any prosthetic material into the patient.

The operative approach in each case has involved either a posterior or medial approach, as detailed in Table 1. We chose a posterior approach over the medial approach as we wanted to send histological and microbiological specimens, which we would have been unable to obtain via a medial approach. It would also enable us to perform an interposition rather than an exclusion bypass, using a shorter conduit and we thought this would be the best method of restoring her anatomy and enable vessel remodeling. The anastomotic technique used in majority of the published reports was interrupted sutures, ensuring long-term patency with future growth, by avoiding “purse-string” effect. Retardation of extremity growth is a major concern in pediatric population and revascularization; hence anastomosis choice needs to be considered. Choice of conduit is another concern. Autologous GSV graft was the preference in the majority of previous cases [1, 3, 4, 14, 15-17], and this would be desirable considering the size mismatch with the use of prosthetic conduit, during the course of growth in children. Having reviewed the limited literature on this topic, we opted for a GSV conduit for our patient as we were unsure whether there was an infectious etiology and this would be our usual conduit of choice in an adult. Femoral vein has been reported [19] as a conduit to treat idiopathic iliac aneurysms in a younger patient due to concern of size mismatch and prophylactic compression stockings were prescribed to prevent chronic venous insufficiency. The patient has so far had graft surveillance for 12 months and she will undergo long-term surveillance until she is an adult. In a case report and review of literature, Halpern et al [20] noted that in cases of multiple idiopathic aneurysms in pediatric age group, the upper extremity arteries are involved in 92% of patients, the aortoiliac region in 92% of patients, and the renal/mesenteric vessels in 77% of cases. Lower limb and cerebrovascular arteries were involved to a lesser extent. Previous case reports have not all documented the use of antiplatelets or anticoagulants following treatment of IPPP, with only one giving low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) alone [2] for at least 3 months and one giving LMWH and aspirin [4] for an unspecified duration of time. Other authors [21] have recommended aspirin for a period of 6 months postoperatively in pediatric non-aortic arterial aneurysms, cognizant of the risk of Reyes syndrome. After consulting the pediatric and hematology teams, we started aspirin in our patient and continued for 3 months.

Conclusions

Pediatric arterial aneurysms, although encountered infrequently, often have an identifiable underlying cause. These etiologies may include iatrogenic factors, connective tissue disorders, or the presence of osteochondromas. However, idiopathic arterial aneurysms affecting the lower extremities remain exceptionally rare in children. These complex vascular diseases necessitate individualized surgical approaches, considering patient age and anatomical factors, while minimizing perioperative risks and ensuring long-term durability. Whilst the evidence base is sparse, the most common management of symptomatic pediatric aneurysms/pseudoaneurysms is open surgical interposition graft repair using autologous GSV and therefore we recommend this modality for treating this unusual presentation. A comprehensive follow-up plan, incorporating non-invasive studies and imaging, is crucial, given the pediatric patient’s overall health and anticipated extended lifespan.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the patient and her parents for consenting to submission of this case report.

Financial Disclosure

This case report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent

Full written consent was obtained from the parents of this patient.

Author Contributions

IA: case report writing and literature review; TA, reporting radiologist: CT images, case report writing; PCB: case report writing, intraoperative imaging, and performed surgery.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

CT: computed tomography; DVT: deep vein thrombosis; GP: general practitioner; GSV: great saphenous vein; IPPP: idiopathic pediatric popliteal pseudoaneurysm; LMWH: low molecular weight heparin; MPR: multi-planar reconstruction; VTE: venous thromboembolism

| References | ▴Top |

- Tolstano A, Lozano E, Cohen-Rios S, Lora-Thomas G, Acevedo-Reyes H, Aguilera L, Maestre-Serrano R. Right idiopathic popliteal aneurysm in a 5-year-old boy: case report. Revista Medica del Hospital General de Mexico. 2021;84(2).

- Sivaharan A, Elsaid T, Stansby G. Acute leg ischaemia in a child due to a thrombosed popliteal aneurysm. EJVES Short Rep. 2019;42:1-3.

doi pubmed - Abich E, Wesley J. Pediatric popliteal artery pseudo-aneurysm: a case report and literature review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021;76:574-576.

- Megalopoulos A, Vasiliadis K, Siminas S, Givissis P, Vargiami E, Zafeiriou D, Botsios D, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the popliteal artery complicated by peroneal mononeuropathy in a 4-year-old child: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37(9):798-801.

doi pubmed - Nasir M, Sadiq I, Abdul Fatir C, Mehmood Qadri H. Spontaneous isolated thrombosed true popliteal aneurysm in an eight-year-old child: a rare case report with literature review. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e28248.

doi pubmed - Platt H. [on an Aneurysm of the Popliteal Artery Caused by an Exostosis of the Femur]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1964;99:8-11.

pubmed - Perez-Burkhardt JL, Gomez Castilla JC. Postraumatic popliteal pseudoaneurysm from femoral osteochondroma: case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37(3):669-671.

doi pubmed - Notrica DM, Amaro E, Linnaus ME, Zoldos J. Unusual cause of acute lower extremity ischemia in a healthy 15-year-old female: A case report and review of popliteal artery aneurysm management in adolescents. J Ped Surg Case Reports. 2016;14:8-11.

- Rangdal SS, Behera P, Bachhal V, Raj N, Sudesh P. Pseudoaneurysm of the popliteal artery in a child with multiple hereditary exostosis: a rare case report and literature review. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2013;22(4):353-356.

doi pubmed - Pavic P, Vergles D, Sarlija M, Ajduk M, Cupurdija K. Pseudoaneurysm of the popliteal artery in a patient with multiple hereditary exostoses. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011;25(2):268.e261-262.

doi pubmed - Al-Hadidy AM, Al-Smady MM, Haroun AA, Hamamy HA, Ghoul SM, Shennak AO. Hereditary multiple exostoses with pseudoaneurysm. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30(3):537-540.

doi pubmed - Nasr B, Albert B, David CH, Marques da Fonseca P, Badra A, Gouny P. Exostoses and vascular complications in the lower limbs: two case reports and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(6):1315.e7-14.

doi pubmed - Onan B, Onan IS, Guner Y, Yeniterzi M. Peroneal nerve palsy caused by popliteal pseudoaneurysm in a child with hereditary multiple exostosis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(4):1037.e1035-1039.

doi pubmed - Asensio JA, Dabestani PJ, Miljkovic SS, Wenzl FA, Kessler JJ, 2nd, Kalamchi LD, Kotaru TR, et al. Traumatic penetrating arteriovenous fistulas: a collective review. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022;48(2):775-789.

doi pubmed - Mohamed A, Tolaymat B, Asham GT, Shen OY, Lombardi JV, Kim T, Batista PM. Popliteal pseudoaneurysm in a young patient with multiple hereditary exostosis. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2023;9(4):101291.

doi pubmed - Lavigne A, Ghali R, Grimard G, Dubois J, Tapiero B. Infected popliteal pseudoaneurysm in a youth basketball player: A case report and brief review of the literature. Vascular. 2024;32(3):648-652.

doi pubmed - Petratos DV, Bakogiannis KS, Anastasopoulos JN, Matsinos GS, Bessias NK. Popliteal artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to osteochondroma in children and adolescents: a case report and literature review. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2009;18(4):205-210.

pubmed - Joshi D, Gupta Y, Ganai B, Mortensen C. Endovascular versus open repair of asymptomatic popliteal artery aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12):CD010149.

doi pubmed - Chithra R, Sundar RA, Velladuraichi B, Sritharan N, Amalorpavanathan J, Vidyasagaran T. Pediatric isolated bilateral iliac aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(1):215-216.

doi pubmed - Halpern V, O'Connor J, Murello M, Siegel D, Cohen JR. Multiple idiopathic arterial aneurysms in children: a case report and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25(5):949-956.

doi pubmed - Davis FM, Eliason JL, Ganesh SK, Blatt NB, Stanley JC, Coleman DM. Pediatric nonaortic arterial aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2016;63(2):466-476.e461.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

International Journal of Clinical Pediatrics is published by Elmer Press Inc.